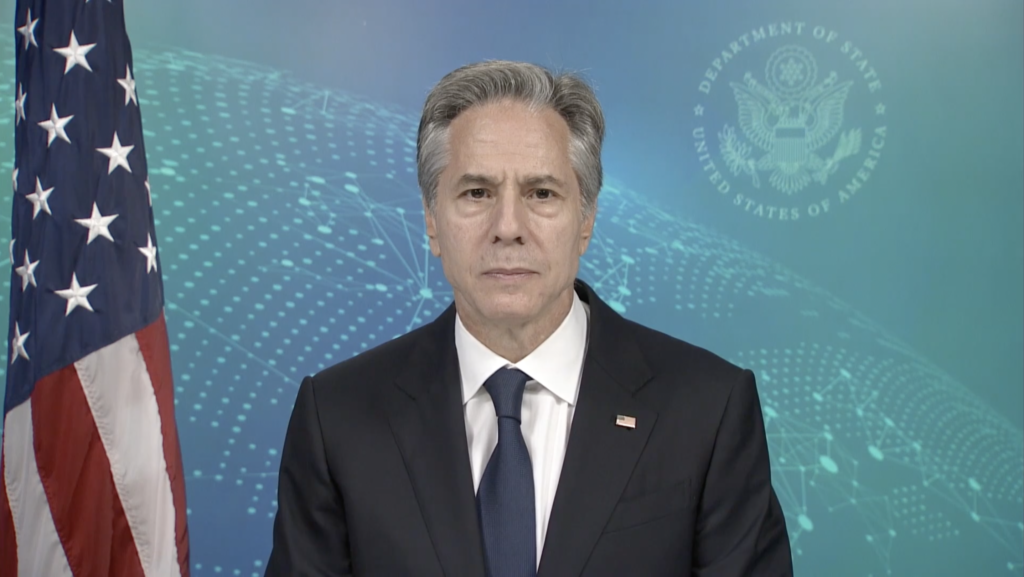

Bialystok, memory of Europe 1943-2023. The official speech of Antony Blinken.

Ambassador of Israel to Poland, Yacov Livne at the Commemorations of the 80th anniversary of Bialystok Ghetto Uprising. Photo © Dawid Gromadzki.

Bialystok, memory of Europe 1943-2023.

The official speech of Antony Blinken.

By Silvia Verdoljak.

On August 16, 2023, in Poland took place the commemoration of the 80th anniversary of the Bialystok Ghetto Uprising against the Nazis: it is the second-largest of its kind, only surpassed by the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of the same year.

Before the invasion, the city of Bialystok had 107,000 inhabitants, about 50,000 of whom were of the Jewish faith. On June 27, 1941, the Germans herded about 2,000 Jews into the Great Synagogue and then set it ablaze. The other Jews were imprisoned in the ghetto. Only 400 survived the deportations and the extermination; among them was Samuel Pisar, stepfather of the U.S. Secretary of State, Antony Blinken.

The Commemoration was attended by the U.S. Ambassador to Poland, Mark Brzezinski, by the Ambassador of Israel to Poland, Yacov Livne, by the civil and religious authorities of the city, and by Antony Blinken himself, with a video. We publish his official speech in English, and our Italian version. The video, with subtitles in English and in Polish, is available on the Department of State’s website (LINK) and on the U.S. Embassy in Warsaw’s Twitter (LINK).

Samuel Pisar’s memoir, “Of Blood and Hope” is also published in Italian, by Sperling & Kupfer with the title “Il sangue della speranza”.

***

Video Remarks at the Commemoration of the 80th Anniversary of the Bialystok Ghetto Uprising

VIDEO REMARKS

ANTONY J. BLINKEN, SECRETARY OF STATE

BIALYSTOK, POLAND

AUGUST 16, 2023

SECRETARY BLINKEN: Thank you for inviting me and my family to be with you on this solemn occasion.

Eighty years ago, no one would have dared to imagine a gathering like this – under the auspices of the mayor of Bialystok, in the presence of the United States ambassador to Poland, a former Polish ambassador to the United States, and Samuel Pisar’s wife – my mother – together with his children and grandchildren.

Survival simply was not in the cards when, on August 16, 1943, hundreds of Jewish men and women in the Bialystok ghetto led an uprising against the Nazis – a rebellion, as one leader put it, to determine how, not whether, they would die.

After crushing the revolt, the Nazis put the last of Bialystok’s Jews onto trains. Among them was my stepfather, Sam, then just thirteen years old, who was sent to Majdanek; his mother to Auschwitz; his little sister Freida likely to Theresienstadt.

How are we to understand this uprising eight decades later? I see it as one of countless acts of resistance by Jews in ghettos and Nazi German concentration camps across Europe – to reject their dehumanization, to reaffirm their dignity. Acts not of futility, but of bravery.

§

Acts like those of Sam’s father, David, who smuggled Jewish children out of the ghetto and weapons into it – for which he was eventually denounced to the Gestapo, and then tortured, killed, and thrown into a mass grave.

Acts like the decision of Sam’s mother, Helaina, made on the day they were deported – forcing her son to wear long pants instead of shorts, despite the blistering heat, so that he’d look more like a man than the boy he was, and so the Nazis would send him to a forced labor camp rather than to a death camp. He often said that, on that day, his mother gave him life for a second time.

For Sam himself, there were many acts of resistance. Surviving in the ghetto; escaping twice after being sent to the gas chamber at Auschwitz – once by picking up a brush and pail and pretending he’d been sent to clean the floors; and, at dawn on a spring day in 1945, breaking away from a Nazi death march and into the arms of American GIs.

He never stopped resisting – by building a new life, a storied career, a family, and by relaying what he had endured from town halls to halls of power.

When the Polish edition of his memoir was first published in the 1980s, he made one of many returns to Bialystok. After speaking at a local high school, students followed him out onto the streets. They wanted him to show them where the ghetto had once stood, and to know what their parents and grandparents did when SS guards herded Jews toward the railway station. “Did they offer you a sip of water?” the students asked. “Did they shed a tear?”

Samuel kept telling his story, even though it was excruciating to relive it, because he felt an overwhelming responsibility to ensure that people never forgot, a responsibility made heavier by the fact that he was the only member of his immediate family – and of hundreds of students in his school in Bialystok – to survive.

As we lose more and more survivors, the responsibility to relay and to grapple with that history passes to all of us. For that reason, I’m grateful to the city of Bialystok, to its leaders, and to its citizens for recognizing this day, among other steps you have taken to ensure coming generations know what happened here.

Like teaching the accurate history of the Holocaust in Bialystok’s schools; and inviting survivors like Marian Turski and Ben Midler to share their experience; and placing a steppingstone outside Sam’s childhood home, inscribed with the names of his murdered family members.

The United States will always be your partner in keeping this history alive. We’re taking another step in that effort by working with our Congress to invest $1 million to help create a virtual tour of Auschwitz-Birkenau so that more people who can’t visit can experience the indelible impact of seeing that site.

So many more markers can and must be placed to educate people about this chapter of human history. For as my stepfather knew, “Never again” was not a guarantee. It was a command, in his words, “to do whatever I can in the struggle for a victory of hope over hate, destruction, and death, forces that can yet again, if [we do] not take care, drive humankind to madness.”

For Samuel, “Never again” was also a call for each of us to ask those difficult questions, not only of our past but of our present, not only of others but of ourselves. What are my acts of resistance? What am I doing in the face of inhumanity?

Of all his efforts to resist the Nazis, the one that I believe made Sam proudest was the act of love, not only surviving himself but building a new family and instilling the lives of those in it with a sense of hope, of freedom, of justice. That was his greatest revenge against Hitler.

So on this day, I know he would be especially moved to see not only his wife and two of his children in Bialystok, but also three of his five grandchildren – Arielle, David, Jeremiah – all doing their part to fulfill the enduring responsibility that, together, we inherit: to make real the command of “Never again.”

The Great Synagogue Memorial: symbolic reconstruction of the destroyed dome of the Bialystok Great Synagogue (Wielka Synagoga w Białymstoku). Photo: © Marcin Jakowiak.

© 19 Agosto 2023